Note: The Corner of 1st & Adventure is reader-supported. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission, all at no cost to you.

Batten Down the Hatches!

As I began to write this article, I was also watching the gusty winds blow through the trees behind our house, as the lights flickered. For several days prior, the weather groups I follow on social media had been talking about the possibility of an arctic blast and lowland snow. It is the heart of winter in the PNW, or what can be more accurately wrapped up as “Storm Season.”

I am a self-proclaimed weather nerd. I used to sketch out my own weather forecasts as a child and always told my teachers I would grow up to be a “weather man.” Skip ahead a few decades…I have no formal schooling or training, but try to learn as much as I can about weather and atmospheric sciences simply because I am so intrigued by it. I love looking at the sky, and the prospect of a good storm gets me all tingly with excitement. And I know there are plenty of others like me.

Much of the rest of the country thinks of “storm chasing” in terms of tornadoes, hurricanes and other severe weather, and the chasing season spans the full calendar. Though we can encounter interesting weather events no matter the month, the big window for storm chasing in the PNW is October through March, when the neighboring Pacific Ocean angrily throws intense storm systems directly at our door. Recently, I had the opportunity to talk with a few of the top weather minds of the Puget Sound region and discuss what it is that makes winter weather around here so intriguing, so unique and so difficult to predict.

Taking the Region by Storm

Everyone I spoke with agreed that the stormy part of the year is the hands-down favorite of the weather community, especially autumn and the transition to winter, with Brie Hawkins of Little Bear Creek Weather highlighting the routine balance of “our classic stormy Pacific Northwest weather, but [also]…some gorgeous frosty mornings that then turn into blue sky days.”

Ben Jurkovich of Washington Weather Chasers summed it up even further, saying, “Lowland snow west of the Cascades does it for me more than anything else.” Needless to say, Ben has been one of the voices most actively sharing updates for the recent and ongoing winter weather, and routinely spends his free time live-streaming as he drives through snowstorms to show everyone the conditions. His 60,000-strong following on Facebook actively contributes with their own observations and snow measurements, while engaging with him during live forecast updates in the evenings.

Outside of loving the beginning and end of each year, there were not a lot of favorable attitudes toward the rest of the months. Scott Sistek of Fox Weather notes “I’m not a fan of summer – just not much for sun and heat.” Whatcom County Weather’s Randy Small doesn’t mince words when he adds “Summer is my 13th favorite season, I don’t like summer.” While I do love sunshine and comfortable temps (right now I’m reminiscing over a January trip to the Florida Keys 2 years ago), I also tend to not be a big summer fan. I love working in my garden, and the availability of alpine hiking or relaxing at the beach, but heat and I do not get along.

From what I glean from social media throughout the year, it seems the active weather of the “ber” months and the early part of the next year tend to be the most popular for the rest of us as well. Cliff Mass, professor of Atmospheric Sciences at UW, quantifies that interest and says he “can tell from [his] blog how many people check in” on snow events and windstorms, but is obviously in agreement with them, continuing “a first-class windstorm is hard to beat,” with Ben Jurkovich adding, “Experiencing the stinger jet of a powerful low on the coast is…super exhilarating.” The various microclimates of the area make for some truly intriguing weather events, and the beauty of a snow storm is hard to beat. Scott Sistek sums up the sentiment, saying, “This area has the perfect balance of it snowing just enough to make you experience its beauty a few times a winter, but not so often that it becomes burdensome or tiring.” Even better still, though our winter temperatures can get quite frigid (like the teens and single digits much of the area experienced the past several days), “it’s still somewhat comfortable…not like 20 below zero where you can’t enjoy anything outside,” he adds, followed by “looking at you, North Dakota.” I spent several years in Bozeman, Montana, where morning lows can drop to -30 or colder, so I know very well the pain Scott is referring to…it seems any temperature below zero feels about the same, it just hurts.

Model Status

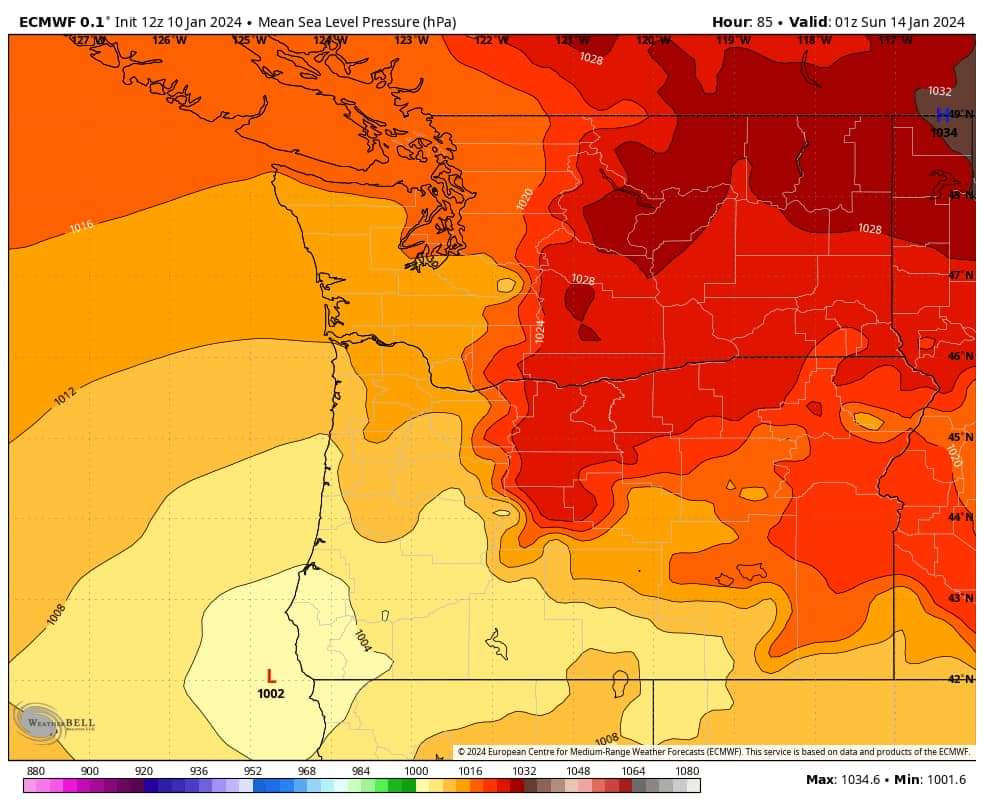

For all you storm lovers who like to sit and watch it all unfold, the meteorological community does the same thing, just starting a little earlier with the forecasting. Ben Jurkovich simply states “weather events just feel different in the Pacific Northwest. They have a unique energy to them.” Along with the occurrence of the event itself, Brie Hawkins notes “tracking model data leading up to the events is fascinating as well…” If you’re unfamiliar with what this looks like, Washington Weather Chasers does an excellent job of showing all the commonly-used computer modeling programs, and explaining how to interpret the data shown (Ben hosts livestreams as new modeling runs come in, and you can rewatch them on his Facebook page). Typically, major models such as the Global Forecast System (GFS) from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction or the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (affectionately known simply as the “Euro” around here) will run an ensemble of dozens of possible storm tracks and outcomes for a particular system, each one taking into account slightly different possibilities. Forecasters then must interpret the data from the full ensemble and determine the most-likely scenario.

It’s a PNW Thing

But for all the sophisticated modeling and improving data collection, the PNW remains a very challenging location to forecast most weather, and is especially notorious for being one of the most difficult places in the country to predict snow. So what makes these events so unique to this area? To put it succinctly, localization and terrain. Whereas many parts of the country can experience the same weather over a broad area, Washington, Oregon and some of the surrounding areas have an extensive network of microclimates, where you might have “extraordinarily different weather just a few miles apart” according to Cliff Mass. Randy Small refers to the significant elevation changes in just a few miles in many areas, with Whatcom County featuring “sea level to the top of Mount Baker within a relatively short distance.” Proximity to the moderating ocean waters adds in an entire additional element as well. Scott Sistek adds “Having an ocean, desert, inland sea and two mountain ranges all within the same region…makes for some amazing microclimates!”

Micro What?

Let’s try to understand some of the common factors around microclimates better:

- Outflow Winds: Think of air or water flowing through a funnel. In the narrow part where the water is squeezed, it flows with force. Once it passes the funnel and can spread out, it flows calmly. This is a good analogy for strong winter winds that can funnel westward through gaps in the Cascade Mountains into places like Gold Bar or Enumclaw, or with the Fraser River outflow in Whatcom County. These areas routinely see high winds for hours, while the lowlands west of them see calm air. The Columbia Gorge east of Portland is known for extreme outflow events, which can bring an entirely different threat of freezing rain or blizzard conditions.

- Hills and Valleys: In many areas around the Puget Sound, hilltops reach over 500 feet in elevation, with nearby valleys significantly lower, or nearby coastal areas at sea level. When it comes to winter weather, the snow level is king, and can often dip down just low enough to brush those hilltops. At my last job, I got in the habit of taking photos of the yard each morning when it snowed, since all my co-workers continually thought I was lying about receiving 2” overnight.

- NW Terminology: Region-specific phenomena like the Olympic Rain Shadow or the *cue Twilight Zone music* Puget Sound Convergence Zone add other influence. The Puget Sound lowlands may receive half an inch of rain during the day, while Sequim sees nary a drop, with the flow of moisture blocked by the Olympic Mountains. And for those living in the Convergence Zone, where the winds flowing around both edges of the Olympics collide, it’s simply a way of life to expect sudden thunderstorms or quick and significant accumulating snow. Scott Sistek marvels that “a 5-mile-wide stretch can be under the most intense of storms for hours…while it’s clear 10 miles north and south of the line.” Were it not for the exact placement of the Olympics, the occurrence simply would not be possible, according to Brie Hawkins.

- This One’s Just Right: Because of the terrain and the ocean influence, the temperatures and conditions have to line up just perfectly to get events like snowfall. Randy Small notes the stark difference between being off by a degree or 2 in summer versus winter, saying, “July predict 76 and it’s 78, nobody notices, but in January, predict 32 with snow but it’s 34 and rain, everyone notices and gets upset,” touching on the “common battle of cold Arctic air and warm ocean air…” Every now and then, conditions line up, with Ben Jurkovich remarking, “When those ingredients come together, it makes arctic blasts and associated snow that much more special.”

In terms of forecasting, those changes, whether significant or subtle, can have an outsized influence on what weather develops, with Brie Hawkins stating “It is nearly impossible to ‘blanket’ forecast for the area because there can be drastic differences…just miles apart.” To complicate things even more, nearly all of our weather comes off the Pacific Ocean, which unfortunately is vast and hard to observe, as Scott Sistek jokes “the fish don’t have email to tell us the weather!” Nationwide, a lot of weather prediction is based on what the weather system has been doing further up the jet stream, explains Randy Small: “Using Kansas as an example, you can just look at the same topography for a vast region, watch storms coming off the Rockies and often be able to predict fairly well how they will act…”

Snow Laughing Matter

But when it comes to the PNW, aside from a handful of satellites watching over the ocean, there is a great absence of observation data to rely on. Weather systems over the ocean are notoriously unpredictable in terms of what track they will follow and how much they will strengthen or weaken. With the most recent potential punch of a snowstorm, the chance of snowfall depended almost solely on where the storm system to our west made landfall…Approach the mid-Washington Coast, and the moisture spreads throughout the Puget Sound Region, bringing widespread snowfall. But the track sagged roughly 150 miles south, and all that moisture instead went into the Portland area, leaving much of the Seattle area high and dry (With the arrival of the arctic front, the Convergence Zone did see some accumulations as moisture lingered into the approaching frigid air, and the north side of the Olympic Peninsula got a nice blanket due to the moisture being squeezed out as the air tried to go up and over the mountains). And early morning last week, another system came in with just enough warm moisture over the top of the cold air already in place to bring a round of freezing rain to much of Western Washington. Again, timing and placement were everything.

Can’t We All Just Get Along?

This unpredictability led to modeling runs spitting out vastly different outcomes (the GFS was adamant for a while that the storm would follow the northern track, while the Euro had Portland in the bullseye). With our winter weather systems, eventually the models tend to align, but often this is last-minute, causing multiple days of changing forecasts; Randy Small adds “that’s why forecasts often have broad ranges like 2-8” of accumulation.” Even then, sometimes the storm will make a last-second change of course, such as a couple years ago when a whopper of a windstorm was all but certain, only to turn sharply north as it reached the coast and take all the energy into Canada.

Side by side comparison of the Euro Model and GFS Model Predictions for the January 13 Storm, courtesy of Washington Weather Chasers Facebook

The good news is the prediction situation is getting better, with Cliff Mass saying, “30-40 years ago was much harder…[but] the models are becoming extraordinarily skillful.” Though snow and wind prediction still needs further improvement, “some of the best forecasting on rainfall in the country” is in the PNW, he adds. Scott Sistek agrees, noting “in the past, living next to the data void of the Pacific Ocean meant that forecast models had a much harder time getting crucial data…Meanwhile, coarse model resolution meant that the computers had trouble figuring out the Cascades and Olympics and their placement adjacent to towns at sea level,” but continues “These days, modern satellites have sensors that can glean observations from clouds and the air that fill in the information gaps, while advancements in computer power allow forecast models to run at much higher resolution…”

Amateurs Wanted

So how does a novice weather enthusiast learn more? One of the great aspects of social media is the amount of information right at our fingertips. Randy Small suggests following those in the know, whether hobbyists or professionals; look for a local Facebook page, such as the one he runs or Brie’s Little Bear Creek Weather. He encourages everyone to ask questions, even if they seem dumb. All of us in the weather community started out knowing nothing, asking and learning is what got us where we are today. A self-taught amateur who developed relationships with the local weather crowds, Randy started his weather page in late 2016, and now has 4 people contributing to the page, which has become so popular that he even has merch available. For further learning, “one of the best and most fun things you can do,” according to Brie Hawkins, “is attend a spotter training class through the National Weather Service.” Other amateur options include CoCoRaHS, which sources precipitation information from hobbyists with backyard weather stations. Even simpler, Brie adds “there are so many books that are great reading on our weather in particular here in the PNW,” with local greats such as Cliff Mass and the late Steve Pool penning some of the great entry books (Steve Pool’s “Somewhere I Was Right” was the first book that truly got me engaged in learning about weather in the PNW).

Book cover photos from Amazon

Steve Pool Somewhere I Was Right Cliff Mass The Weather of the Pacific Northwest

Location, Location, Location

Until we can get the fish to email us back, sometimes the best we can do is just let the systems roll and enjoy whatever excitement they bring. The great aspect of the PNW is a wealth of exciting spots to experience the weather. But finding the best places takes a little investigating, with Scott Sistek explaining, “Look back at past storms and their impacts – they’re likely to be the best place to find that weather again.” If you want “big storms,” Cliff Mass simply says, “head for the coast,” with Ben Jurkovich adding, “The Oregon Coast and the Southwest Washington Coast is incredible during a strong landfalling surface low.” Cape Disappointment features some of the most impressive waves in the region, while Westport offers a viewing tower above the beach to safely watch the breakers against the jetty.

Closer to Seattle, Scott Sistek likes the Mukilteo Lighthouse Park, saying, “During windstorms you get the bonus of watching the Mukilteo/Whidbey Island ferry fight the winds and waves – it’s a sight to behold!” A few years ago, Ivar’s Mukilteo Landing restaurant had a truly personal experience with the fury of a storm, as wind-blown waves crashed through the restaurant windows and tore through the dining area! Across the water, having access to the beaches of Whidbey Island as a child are some of my fondest storm memories, as we would bundle up and watch the rollers crash into the jetty at the Keystone Ferry terminal south of Coupeville. Switching to the outflow winds, Brie Hawkins notes, “the Columbia River Gorge is a super fun place to go and experience strong [east] winds,” while Randy Small tends to stick to Whatcom County, saying it “is the catalyst for winter weather…[and] the central area featured in just about every storm…[with] ice storms, wind, or major flooding.”

On that note, another winter weather event of great interest in the weather community is flooding. Western Washington is no stranger to high rivers during bouts of heavy rain courtesy of atmospheric rivers originating in the tropics. Several of the east Puget Sound rivers are fairly reliable for flooding during these events, such as the Snoqualmie, Stillaguamish, Skagit and Skykomish. Viewing floodwaters up close should be done with great care and from a safe vantage point. The overlooks at Snoqualmie Falls are a local favorite for watching the roaring cascade, while farther north, the old train bridge on the Centennial Trail in Arlington provides a great panoramic view of the North and South Fork Stillaguamish colliding in fury.

Coming Up With Weather Tidbits is a Breeze

As we continue to thaw out from this recent bout of winter weather, let’s wrap things up with a few more interesting points about the weather and climate of the region. First, while most of the country experiences severe weather (the “Severe” designation is based on National Weather Service criteria), the PNW is relatively free from most of it. Scott Sistek notes “the lack of thunderstorms and tornadic storms is quite unique to the I-5 corridor.” When summer temperatures drop with a marine push, we might get “a touch of fog and drizzle…[while] back east, those fronts come with a stormy price.” Cliff Mass adds that, while hurricanes don’t happen here and tornadoes are rare, “a vast range of events are accessible here” compared to other parts of the country, especially with Eastern Washington included. Brie Hawkins follows up on the hurricane note saying, “our windstorms are unique in that…we can get storms that bring strong [sometimes hurricane-force] winds, and with our tall trees, the impacts can be quite large…” Randy Small also mentions the unique aspects of winter storms here, but with snow in Whatcom County, with the “outflow, snow, blizzard-type activity…with sustained 40-50 mph winds,” though blizzard warnings are exceptionally rare in the region (the warning issued for the Cascades a couple weeks ago was the first in 10 years).

Finally, to close on a fun fact, courtesy of Scott Sistek, “Seattle was the perfect Fahrenheit scale – hottest [recorded] temperature was 100 and the coldest was 0. Guess that’s no longer the case – thanks, 2021 heat wave!”

All photos and content © Eric S. Allan 2016-2024 unless otherwise noted. All photos with people used with permission.

For media and publication inquiries: eric@corneroffirstandadventure.com

Leave a comment