They lived down the street and worked in the community. Friends and neighbors, local farmers and businessmen. How quickly things change during a state of fear and suspicion. On February 19, 1942, life was upended for thousands of Americans of Japanese ancestry or origin.

Shortly after the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War “to prescribe military areas…from which any or all persons may be excluded…[and] authorized to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter or other accommodations as may be necessary…” In short, President Roosevelt was laying the groundwork for the roundup and forcible removal of Japanese Americans from their homes, their race being deemed a threat to national security. All told, about 120,000 people were sent to internment camps operated by the War Relocation Authority, approximately two-thirds of which were American citizens.

This is not my story to tell. I am so incredibly privileged to have never known discrimination or mistreatment on the basis of my race, religion, or any other part of my identity. I do not know what it is like to experience that kind of treatment, and I realize my words or attempt to understand can never come close to the true reality that so many Japanese Americans endured during the war. But I can do my part to learn and recognize the dark chapters in our country’s history, and I can teach my own children, so that we may never repeat it.

Across the Puget Sound from Seattle lies a 10-mile long island showcasing native forestlands, farms and scenic beaches, just a quick hop from the Olympic Peninsula. Today, Bainbridge Island hosts a vibrant art scene, upscale food and drink options, and a diverse community. A popular little sport was even invented there. It’s called pickleball; you may have heard of it?

In the early 1940s, the island was less-populated and trendy, but still home to a robust and diverse community. My grandparents operated a historic theater in the small community of Lynwood Center; my mother grew up with many kids of various ethnic backgrounds. About 275 of the 3,000 residents were of Japanese descent; most were strawberry farmers and small business owners.

After the issuance of Executive Order 9066, Bainbridge Island was the first community to be addressed, due to proximity to Puget Sound military installations. Residents were given 6 days notice, and then shipped off the island via ferry, destined for camps in the interior West. Once the war ended, over half returned to the island, to mostly positive and welcoming Bainbridge Island residents, but with a long road to recovery and healing ahead.

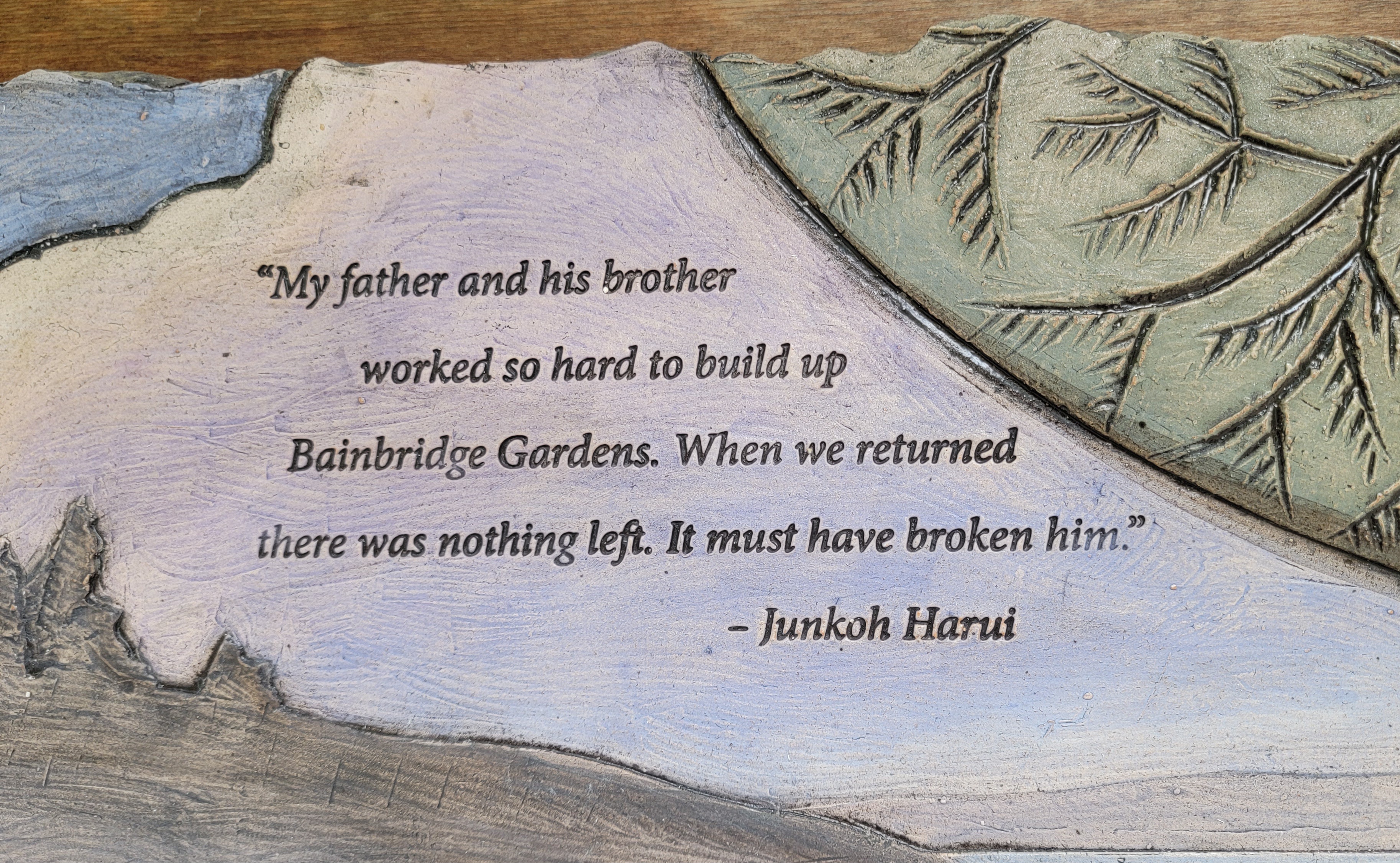

Today, one of the best places to learn about the entire tragic and abhorrent ordeal is the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, operated by the National Park Service in conjunction with Minidoka National Historic Site, and an official Wing Luke Museum Affiliated Area. Located near the Eagledale dock where the incarcerated residents were loaded onto the ferry, the site features a beautiful memorial wall for reflection, education and mourning. Officially opened to the public in July 2011, the grounds incorporate native plants, origami cranes and various interpretive art pieces.

The full experience is sobering, grounding and heavy. Other emotions I’ve heard used to describe it are anger, heartbreak and determination. None of this experience comes close to the reality of 1942 and beyond, but with every hurtful moment, we can learn. We can vow “Nidoto Nai Yoni” (Let it not happen again).

I strongly encourage a stop here on your next visit to Bainbridge Island, especially if you have children old enough to understand what happened. As with any memorial, sacred space or place of reflection, please show respect for the land, the people, the culture and the history. The memorial is located at Pritchard Park, on the south side of Eagle Harbor, just minutes from the Seattle-Bainbridge Ferry. More information is available on the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community website or the National Park Service website.

Leave a comment